Just as the new school year was about to start in the summer of 2020, UWC ISAK Japan students had a special opportunity of learning from the Ainu of Japan. A group of our students hosted a representative of the Ainu community in a discussion on “Being Ainu.” For many, it was our first exposure to the rich history and traditions of Japan’s unique indigenous ethnic group. Little did I know that this was the beginning of my journey of discovery … and I wasn’t even there!

Just as the new school year was about to start in the summer of 2020, UWC ISAK Japan students had a special opportunity of learning from the Ainu of Japan. A group of our students hosted a representative of the Ainu community in a discussion on “Being Ainu.” For many, it was our first exposure to the rich history and traditions of Japan’s unique indigenous ethnic group. Little did I know that this was the beginning of my journey of discovery … and I wasn’t even there!

My introduction to Ainu culture

I arrived in Japan as a new faculty member for the 2020-21 school year. I would have already arrived on campus by early August in a typical year, but travel and visa restrictions held me back. However, I eventually made it to Karuizawa, and that is where I started to pick up on some of the buzz from the Being Ainu event.

I arrived in Japan as a new faculty member for the 2020-21 school year. I would have already arrived on campus by early August in a typical year, but travel and visa restrictions held me back. However, I eventually made it to Karuizawa, and that is where I started to pick up on some of the buzz from the Being Ainu event.

I learned from students and colleagues about Sekai Education—an initiative founded by Kai Childs that aims to expand students’ worldview by connecting education to the real world. Kai worked with students to organize the Being Ainu event and became an incredible resource in my own education and opportunities for our students.

Incorporating cultural discussions into education

At UWC ISAK, I teach social studies and history, and I saw an opportunity to learn from the Ainu of Japan and begin a discussion with our students and representatives of the Ainu community. Again, Kai masterfully coordinated a panel discussion with Ainu leaders. This gave our students a deeper understanding of their culture and what it means to be Ainu in modern Japan.

At UWC ISAK, I teach social studies and history, and I saw an opportunity to learn from the Ainu of Japan and begin a discussion with our students and representatives of the Ainu community. Again, Kai masterfully coordinated a panel discussion with Ainu leaders. This gave our students a deeper understanding of their culture and what it means to be Ainu in modern Japan.

At this point, my appetite for learning more about the Ainu was growing by the day. Joined by my colleague Daisuke Masui, who teaches Japanese at UWC ISAK and shares my enthusiasm for Ainu culture, we embarked on a professional development visit to an Ainu community in Nibutani, in still-frigid Hokkaido.

Embarking on a journey of discovery to Hokkaido

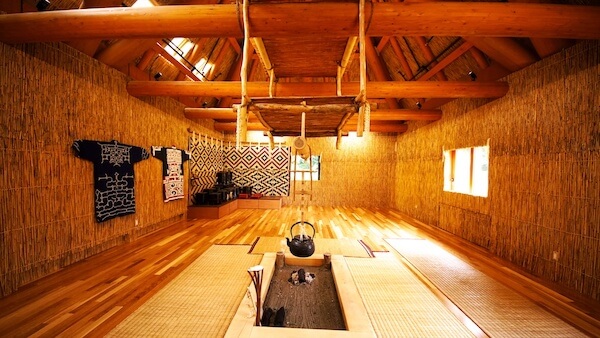

Nibutani lies on the banks of the Saru River in Hokkaido, where it hosts an active and hospitable Ainu community. Ainu, which means “human” in the Ainu language, perfectly captures the essence of the people I had the honor of meeting during my visit. Yet again, Kai Childs facilitated our activities in Nibutani, which included skill sharing, discussions of educational experiences, and opportunities, but particularly listening. Once again, I took on the role of student and focused on learning as much as I could.

Nibutani lies on the banks of the Saru River in Hokkaido, where it hosts an active and hospitable Ainu community. Ainu, which means “human” in the Ainu language, perfectly captures the essence of the people I had the honor of meeting during my visit. Yet again, Kai Childs facilitated our activities in Nibutani, which included skill sharing, discussions of educational experiences, and opportunities, but particularly listening. Once again, I took on the role of student and focused on learning as much as I could.

Gaining a deeper understanding of respect for elders

Ryo Yonezawa and Maya Sekine, two people UWC ISAK Japan have had the opportunity of working with before, were pivotal in making introductions to members of this community and sharing the deep rich knowledge of the Ainu culture and history. Kamuy, for example, I previously understood to be gods but instead learned that it better represents the spiritual or divine entity in all things. Masui Sensei asked Maya-san if the language differentiates between animate and inanimate objects, like the Japanese language does with ある and いる, to which we learn that it does not.

Ryo Yonezawa and Maya Sekine, two people UWC ISAK Japan have had the opportunity of working with before, were pivotal in making introductions to members of this community and sharing the deep rich knowledge of the Ainu culture and history. Kamuy, for example, I previously understood to be gods but instead learned that it better represents the spiritual or divine entity in all things. Masui Sensei asked Maya-san if the language differentiates between animate and inanimate objects, like the Japanese language does with ある and いる, to which we learn that it does not.

Modern interpretations of Ainu art and culture

Next, we met Maya-San’s family, her grandmother, Yukiko Kaizawa and mother, Maki Sekine, Ainu artisans, and her father, Kenji Sekine, an Ainu language teacher. Discovering the meanings behind the various patterns and styles one might typically see in Ainu arts brought a sense of uniformity in a seemingly disconnected world. Maki-San stressed the importance of how Ainu patterns never breaking conveys a sense of perpetual connection. Maki-San’s union can best explain the depth of this connection with Kansai-raised Kenji-San. Upon learning of the Ainu, he dedicated his life to keeping the Ainu language alive and spoken. For more than 20 years now, Kenji-San employs, amongst many strategies, the linguistic pedagogical methods of the Maori to demonstrate that language shapes a part of our identity, daily life, and history.

Next, we met Maya-San’s family, her grandmother, Yukiko Kaizawa and mother, Maki Sekine, Ainu artisans, and her father, Kenji Sekine, an Ainu language teacher. Discovering the meanings behind the various patterns and styles one might typically see in Ainu arts brought a sense of uniformity in a seemingly disconnected world. Maki-San stressed the importance of how Ainu patterns never breaking conveys a sense of perpetual connection. Maki-San’s union can best explain the depth of this connection with Kansai-raised Kenji-San. Upon learning of the Ainu, he dedicated his life to keeping the Ainu language alive and spoken. For more than 20 years now, Kenji-San employs, amongst many strategies, the linguistic pedagogical methods of the Maori to demonstrate that language shapes a part of our identity, daily life, and history.

On the day before we departed Nibutani, amidst a break in the rain, we met with wood craftsman Toru Kaizawa and hunter Atsushi Monbetsu. In a studio surrounded by pop culture from across the world within a workshop of traditional Ainu symbols, Toru-San translates modern influences into his artwork. Rather than feeling nostalgic, his approach speaks to the living and breathing culture and identity of the Ainu. This sentiment was shared by Monbetsu-San when it comes to the outdoors, sharing his belief that there are particular ways of combining modern living with outdoor education to learn specific knowledge systems sustainably. Fumio Kimura is an activist, at almost 70 years of age, hoping to return the more than 1600 ancestral remains taken from the graves of the Ainu. I highly recommend the documentary Colonized Voices to learn more about the Ainu and the current issues the community is facing.

On the day before we departed Nibutani, amidst a break in the rain, we met with wood craftsman Toru Kaizawa and hunter Atsushi Monbetsu. In a studio surrounded by pop culture from across the world within a workshop of traditional Ainu symbols, Toru-San translates modern influences into his artwork. Rather than feeling nostalgic, his approach speaks to the living and breathing culture and identity of the Ainu. This sentiment was shared by Monbetsu-San when it comes to the outdoors, sharing his belief that there are particular ways of combining modern living with outdoor education to learn specific knowledge systems sustainably. Fumio Kimura is an activist, at almost 70 years of age, hoping to return the more than 1600 ancestral remains taken from the graves of the Ainu. I highly recommend the documentary Colonized Voices to learn more about the Ainu and the current issues the community is facing.

What I learned from the Ainu of Japan

My journey to Hokkaido was one of the most incredible experiences I have had, both personally and as an educator. As I sought to learn from the Ainu of Japan, I learned from the deep well of stories, experiences, and philosophies of our Ainu community hosts the value of courageously tackling uncomfortable histories. I learned the importance of celebrating living histories through culture like art, language, and appreciation of the outdoors.

My journey to Hokkaido was one of the most incredible experiences I have had, both personally and as an educator. As I sought to learn from the Ainu of Japan, I learned from the deep well of stories, experiences, and philosophies of our Ainu community hosts the value of courageously tackling uncomfortable histories. I learned the importance of celebrating living histories through culture like art, language, and appreciation of the outdoors.

Why being a leader is so valuable

At UWC ISAK Japan, we aim to create an environment where students learn to identify what is most important and needed, take action in the face of discomfort, use diversity as a strength, and support others in this practice. The people I met in Nibutani epitomized this type of leadership and reinforced my belief in the mission of UWC ISAK. It has also fueled my desire to deepen my understanding of other cultures, including the Ainu of Hokkaido, and build meaningful and productive relationships.

At UWC ISAK Japan, we aim to create an environment where students learn to identify what is most important and needed, take action in the face of discomfort, use diversity as a strength, and support others in this practice. The people I met in Nibutani epitomized this type of leadership and reinforced my belief in the mission of UWC ISAK. It has also fueled my desire to deepen my understanding of other cultures, including the Ainu of Hokkaido, and build meaningful and productive relationships.

イヤイライケレ! (“Thank you” in Ainu)

by Taymour Bouran (Instructor, History/Social Studies)